- Home

- Lin Oliver

Zero to Hero Page 3

Zero to Hero Read online

Page 3

“Speak for yourself,” Billy muttered as they pulled away from the curb.

The supermarket was quiet that early on a Sunday morning. Billy grabbed a cart and followed his mom up and down the aisles while she filled it with useful things like canned soup, flour, sugar, bread, maple syrup, and whipped butter. She didn’t object when he tossed in some of his favorite foods: chunky peanut butter, strawberry jam, frozen waffles, packaged miso soup, tuna fish, and cans of little green peas. As they were rounding the corner of Aisle 9 and heading into the paper-goods section, Billy heard the loudspeaker microphone clicking on.

“Good morning, shoppers,” a voice said. “I want to introduce you to someone brand-new to the neighborhood. Billy Broccoli is in the house.”

Billy stopped dead in his tracks. He knew that voice. It belonged to a certain ghost he had met the night before. He glanced over at the checkout counter and saw that the microphone for the public address system had left its metal clip holder and was bobbing up and down in midair.

“That’s him, Mom.”

“That’s who, honey? You didn’t tell me you had already made a friend in the neighborhood. Oh, look, there’s a bakery here right in the market. I’ll go get some sticky buns while you say hi to your new friend.”

And with that, she was off. Billy looked around, but he saw no sign of Hoover. Suddenly, a flurry of plastic picnic plates came flying down the aisle like a bunch of Frisbees heading right toward him. He tried to catch them, but they were coming fast and he could only manage to grab a few out of the air.

“You need to work on your hand-eye coordination, Billy Boy.”

Suddenly, Hoover Porterhouse appeared out of thin air. He stood in front of Billy, holding the torn package of plastic plates.

“You wait right here,” Billy said to him. “Do not drift. Do not move. Do not fly. I’m going to get my mom so she’ll see you and know you’re real.”

“Can’t happen, Billy Boy. She won’t see me. I’m invisible.”

“No, you’re not. How could you be? I’m looking at you right now.”

“You can see me because I’m your ghost. To everyone else, I’m invisible.”

“You’re not my ghost! I never asked for a ghost. I asked for an iPod, I asked for my own cell phone, I asked for a red BMX bike with black trim. But never, on any list, at any time, anywhere, did I ever ask for a ghost.”

“Lucky you. I show and you didn’t even have to ask. You hit the jackpot, ducky.”

Hoover drifted over to the shopping cart and floated right through the metal slats to perch on the kiddy seat.

“I used to love this stuff,” he said, picking up the jar of peanut butter. “Yes, sir, peanut butter was one of the great things about being alive. Everyone in town knew that the Hoove was a peanut-butter hog.”

“You call yourself the Hoove? Seriously?”

“No, not seriously. I don’t do anything seriously. Bring the cart and follow me. I’ll let you feast your eyes on some Hoove-style fun.”

Hoover whooshed down the paper-goods aisle, turned the corner, and stopped in front of the seventy-two choices of breakfast cereals. He picked out three family-size boxes and held them in his hands.

“I need your undivided attention,” he said to Billy. “First, I will disappear. Second, I will juggle these three boxes.”

Hoover began to whistle “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,” and in the blink of an eye, he disappeared. Suddenly, the three cereal boxes rose into the air and started circling one another, slowly at first, then faster and faster until Billy could barely tell one box from the other.

“Now watch this,” the Hoove called out. “I’m going high.”

Still circling one another, the boxes rose higher and higher into the air, until they were so close to the ceiling, they actually bounced off the fluorescent light fixtures. Without a doubt, it was an impressive trick.

“Could you stop doing that?” Billy called out. “You’re going to get me thrown out of the market.”

The three boxes fell from the air, landing in the cart, one right after the other. Billy looked around for the Hoove.

“Are you still here?” he asked.

“Of course I’m still here,” Billy’s mother said, returning from the bakery with a bag of sticky buns. Then, glancing in the cart, she added, “That’s quite a lot of cereal for just the four of us.”

Billy knew his mother didn’t want to hear about his cereal-juggling ghost buddy, so he thought fast.

“I heard on TV that if you go shopping when you’re hungry, you buy twenty-two percent more food,” he said. “I guess I should have eaten breakfast first.”

After that, Hoover kept himself scarce. He wasn’t in the fruit section. Or at the checkout counter. Or in the parking lot. Billy helped his mom load the groceries into the car and they pulled out of the parking lot and drove down Ventura Boulevard. When they stopped at a red light near their house, Billy noticed a familiar face outside his window. The strange thing was, it was upside down and sliding down the glass. And if that wasn’t enough, it was smiling.

“Hey, ducky,” the Hoove said through the glass.

“Mom!” Billy yelled out urgently. “Look out my window and honestly tell me you don’t see a face there.”

Mrs. Broccoli-Fielding slipped her glasses down from the top of her head and looked out the passenger-side window.

“Listen to me, Billy. What I honestly see is a side-view mirror, some palm trees, a silver parked car, and a teenage girl walking along the sidewalk whose skirt is definitely too short. What is her mother thinking? Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to keep my eyes on the road.”

The light changed to green and Mrs. Broccoli-Fielding continued down Ventura Boulevard. Hoover had now righted himself to a sitting position and was traveling at the same speed as the vehicle, while holding his cap so it wouldn’t blow off in the wind.

“This was a fun little joyride,” he called out. “But I got things to do, places to go, people to see.” And with that, he somersaulted back up in the air and disappeared from Billy’s view.

One of the Hoove’s favorite Sunday excursions was to float into Mrs. Moreno’s house and rearrange her furniture while she was out for her 1.3-mile jog. She was a slow runner, and that gave him plenty of time to work on at least the living room. But as he headed to her house, he realized that he wasn’t in the mood for a prank. He had worn himself out trying to entertain the new kid. In all his ninety-nine years of being a ghost, he had haunted fourteen kids, but he’d never seen one so tightly wound. He was going to have to teach this Billy Broccoli kid a thing or two about having fun if they were going to be roommates.

One thing he knew for sure. If that guy was expecting to start a new school, make friends, and fit in, he was going to have to get something going in the fun department. No one wanted to be around a Goody Two-Shoes like his sister Mary-Margaret had been, who never went anywhere or did anything. And going places was high on Hoover’s To Do list. But the Higher-Ups said that until he passed all the subjects on his report card, he couldn’t leave the boundaries of his family’s original ranchero. The problem was, he kept failing miserably at Responsibility and Helping Others. He was starting to feel the pressure now, because if he didn’t pass all his subjects within one hundred years, he’d be permanently grounded. Then he’d be stuck on his family’s property for eternity.

But rather than worry about his grades, the Hoove decided that he was in the mood for a movie. Lucky for him, the Cineplex was within the boundaries that made up the ranchero. Actually, only half of the movie theater was, which meant he could only see films that played on screens 1, 3, and 7. The others were off-limits, a rotten break for him because he had never seen any of the Batmans. They always played on Screen 5.

On the way to the theater, he was distracted by hoots, whistles, and screams coming from across the street. Two Little League teams were playing a baseball game in Live Oak Park. If only he could go there, throw a few pi

tches, and take a few swings, he’d have been the happiest ghost on Ventura Boulevard. But the park was beyond the boundary lines. He’d been warned by the Higher-Ups that if he stepped over the line, he would instantly disappear. Dematerialize. Cease to be.

Hoover watched the kids play for a while but soon became frustrated. When he was alive, he’d been a pitcher for the San Fernando Junior Cougars, way back when baseball was new. Now he could feel his hands itching to throw a fastball. He knew if he stayed there another second, he would zip over the line into the no-man’s-land of the park. Then he’d never have a chance to earn his ghostly freedom.

The Hoove put himself into hyperglide and zoomed in the opposite direction. His usual form of transportation was float mode. When he needed to make good time, he went into the Swoosh. But when speed was of the essence, he kicked into hyperglide. He didn’t use it all that often because it messed up his hair, but his need to get away from the park was intense, so hyperglide it was.

Since nothing good was playing at the movie theater, he decided to return to Billy’s house. The Broccoli-Fieldings had just finished eating Sunday brunch at the backyard picnic table. The Hoove floated around the table, noticing remnants of pancakes, cheese omelets, Swedish meatballs in a mushroom cream sauce, and sticky buns scattered on each plate.

“Do you guys ever wonder why a meatball that looks like a meatball is called Swedish?” Billy was asking the other members of the family. “I mean, did some Swedish guy discover the meatball while cross-country skiing?”

Billy picked up a leftover meatball on his plate, held it to his ear, and listened.

“Nope,” he said. “I don’t hear a Swedish accent.”

Billy thought his joke was hysterical, but the Hoove just shook his head. Any guy who loves meatball humor is going to have a rough go of it at a new school, he thought.

“Since we’re on the topic of meatballs,” Breeze was saying, “can I make one tiny suggestion? Let’s not have them again. Has anyone here noticed that when they cool off and the sauce congeals, it looks a whole lot like cow dung?”

“I think they’re delicious,” Dr. Fielding said, reaching out to his wife and putting his hand warmly over hers.

When Billy excused himself and headed for his room to prepare for the first day of school, the Hoove floated over to his tree. It was an old, seventy-foot-tall live oak tree that stood at the very end of the Broccoli-Fieldings’ backyard. The Hoove’s father, Hoover Porterhouse II, had planted it when his son was born, and the whole Porterhouse family had referred to it as the Birthday Tree. As the ranch was sold off and houses sprung up where there once had been orange groves, the tree had miraculously escaped the bulldozer. It had always been Hoover’s favorite climbing tree, and over the last ninety-nine years, it had become his favorite sitting tree.

He drifted up to the top branch, looking forward to a lazy afternoon spent watching the squirrels scurry around in search of acorns. Suddenly, a strong wind arose and carried him over to the trunk, where he saw a knife chiseling a message into the bark. It said, Progress Report.

“Progress report! Already?” The Hoove groaned. “I just got my report card yesterday. Can’t you guys give it a rest?”

“Time is running out,” he thought he heard the wind say. Then an unseen hand grabbed him by the scruff of the neck and held him.

“Okay, okay,” he said. “I’ll read it. You don’t have to get physical.”

The knife continued carving until the words Helping Others appeared on the tree trunk. The next word the knife wrote was Fail.

“Aw, come on,” the Hoove argued. “I deserve at least a D. Today I helped a senior citizen find his false teeth. They fell out when he was crossing the street. That’s got to count for something.”

There was no answer. Instead, the word Fail lit up, blinked twice, then disappeared in a blaze of fire, leaving the trunk as if nothing had happened.

“Now I’m never going to see them.” Hoover pouted.

The them he was referring to were the baseball fields of America. Hoover Porterhouse’s dream had always been to see a game at every Major League baseball stadium. It was the one thing he longed for more than anything.

“What am I supposed to do now?” he wondered aloud. “Will you guys please give me a sign?”

At that very moment, Billy Broccoli walked out the back door of his house, carrying a pair of jeans and a tennis racquet. He threw the jeans over the clothesline and started to beat them with the racquet. Dust flew all over and scraps of paper and gum wrappers dropped out of the pockets. Billy started to cough and he hacked so hard, it sounded like he had a fur ball stuck in his throat. His eyes watered, his nose ran, and the racquet flew out of his hand as he dropped to the ground, attempting to catch his breath.

The Hoove tried to look away, but the wind kept turning his head so that all he could see was Billy.

“No!” he called out. “I refuse! Please tell me this isn’t my sign!”

But it was his sign, and he knew it. The Higher-Ups were speaking to him, telling him that Billy Broccoli was his project. If he ever wanted to see those baseball fields, he was going to have to be responsible and help Billy become the person he wanted to be. Hoover gave a mighty sigh, letting out so much cold air that some of the leaves on the branch actually froze.

He had better start now. There was no time to waste.

Billy Broccoli was no easy assignment.

CHAPTER 5

By the time the Hoove returned to the house, Billy was back in his room, preparing for his first day of school. The Hoove wafted in through the window and perched himself on top of the bookshelf, the one that was painted in rainbow colors to match the rainbow ponies on Billy’s wallpaper. He sat there silently, shaking his head as he watched Billy trying on the clothes he wanted to wear for the first day of school.

First, Billy slipped on a red T-shirt, tucked it into his jeans, and pulled his jeans up high on his waist, the way he liked to wear them. He tightened his belt and put it on the fourth notch, just to make sure that nothing was going to slip. He looked at himself in the mirror, assumed what he thought was an ultracool pose, and nodded with satisfaction.

“Don’t even think about it,” the Hoove said, startling Billy so much that he might have actually jumped out of his jeans if they hadn’t been pulled up almost to his chin.

“I don’t see anything wrong with the way I look,” Billy said, more than a little insulted.

It was time for the Hoove to get to work. He shot off his perch and, in an instant, stood between Billy and the mirror.

“Let me ask you a direct question, Billy Boy. What do you see when you’re staring in that mirror?”

“I see me. Looking pretty good.”

“Well, that makes one of us.”

“Why? What do you see?”

“First off, I see a guy whose pants are so high that they might as well be a chin bib, and whose belt is so tight that his voice is going to become soprano any second.”

“Are we looking in the same mirror?” Billy asked. He couldn’t believe he was being so thoroughly criticized.

“No, I’m looking directly at you,” the Hoove said. “You’re anything but a babe magnet. Just check out your T-shirt, for example.”

Billy looked at himself in the mirror. The tee, which he had ordered online from his favorite joke T-shirt company, read VARSITY FARTING TEAM! The exclamation point was a little puff of smoke. Billy thought fart T-shirts were hilarious. So hilarious that he owned at least four or five of them.

“This shirt is going to crack everyone up,” Billy said. “I’m going to have ten friends before I even get to homeroom.”

“Okay,” the Hoove said. “Picture this. You walk through the school’s front doors for the very first time wearing that shirt. A group of the cutest sixth-grade girls in the twelve western states is standing before you. What do you think happens next?”

“They read my shirt and immediately want to know who the funny new gu

y is.”

“Correction. They read your shirt and run away from you so fast you won’t even be able to see their ponytails bobbing up and down in the distance.”

“Really? You think so?”

“I know so. I appreciate a good intestinal joke myself, but I am certain that of all the things girls think are funny, expelling gas is not in the top five hundred. So do me a favor. Loosen the belt. Lower the pants. And show me a shirt with no writing on it.”

“What do you know, anyway?” Billy said as he loosened his belt. “You’re more than one hundred years old. What was cool back then isn’t what’s cool now.”

“What little you know, Billy Broccoli. Cool is cool. Cool is forever. I know this because … did I mention this? … I invented it. My middle name is Cool.”

The Hoove floated over to the closet and picked out a dark green T-shirt and a brown hoodie. Billy tried them on together.

“There it is!” the Hoove said, nodded approvingly. “We’re at least on the runway to normal. People might actually want to have a conversation with you now. And by the way, make sure you don’t have any carrots or spinach in your teeth. The Hoove’s Rule Number Thirty-three is ‘Never approach a social gathering with a vegetable garden stuck in your teeth.’ ”

“You have a rule for that?” Billy asked.

“I got rules coming out of my ears, and you’re going to benefit from every one of them. Let’s start from the beginning. Rule Number One: ‘If a dog starts to sniff behind your knees in the presence of a young lady … especially a redhead —’ ”

“Listen, Hoove, I don’t care about sniffing dogs and tooth vegetables. I have to organize my notebook for tomorrow.”

“Excuse me, I think I’m falling asleep.” The Hoove faked a yawn.

Billy sat down at his desk while the Hoove looked around for something more interesting to do. He picked up a Ping-Pong paddle and a fluorescent orange Ping-Pong ball on Billy’s shelf and started to hit the ball against the wall.

Ping. Pong. Ping. Pong. Ping. Pong.

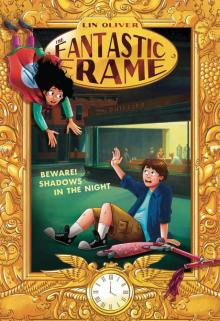

Beware! Shadows in the Night

Beware! Shadows in the Night Almost Identical #1

Almost Identical #1 Two-Faced #2

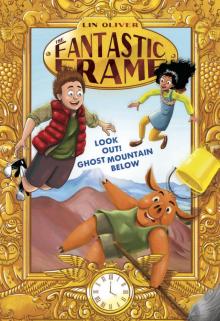

Two-Faced #2 Look Out! Ghost Mountain Below

Look Out! Ghost Mountain Below Zero to Hero

Zero to Hero Always Dance with a Hairy Buffalo

Always Dance with a Hairy Buffalo Danger! Tiger Crossing

Danger! Tiger Crossing Twice As Nice

Twice As Nice Double-Crossed

Double-Crossed Splat! Another Messy Sunday

Splat! Another Messy Sunday The Shadow Mask

The Shadow Mask