- Home

- Lin Oliver

Zero to Hero

Zero to Hero Read online

GHOST

BUDDY

ZERO TO HERO

HENRY WINKLER

AND LIN OLIVER

To Debra Dorfman, whose favorite word is “yes.”

And to Stacey always. —H.W.

For Debra Dorfman, who brought

Ghost Buddy alive. —L.O.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Preview

About the Author

Copyright

CHAPTER 1

Billy Broccoli wasn’t getting out of the car. He had warned them. In fact, he had spent a month and a half warning them. Forty-five days to be exact. He had said, “You can move to the new house. I support that decision wholeheartedly. Just don’t ask me to move with you. I can’t and I won’t.”

“Billy, that’s enough,” his mother said, tapping her foot impatiently. “You’ve made your point. Now get out of the car.”

“No, thanks, Mom.”

“Billy. I understand how you’re feeling. It’s normal for a child to resist change.” His mother, Charlotte Broccoli-Fielding, was a middle-school principal and knew all there was to know about middle schoolers. Or so she thought. The only hole in her knowledge was her own son.

“First of all, Mom, I am no longer a child,” Billy said to her. “I’m eleven going on twelve, which makes me officially a tween. Not only do we have our own television shows, but I have my own mind … which, by the way, is insisting that I stay in the car.”

Billy rolled up the window to end the conversation.

“Well,” Dr. Bennett Fielding said, “I guess Bill has certainly let us know where he stands. Let’s give him some time, and I’m confident he’ll make the right decision and come in the house.”

Dr. Fielding was Billy’s new stepfather, having married Billy’s mother only eleven days before. He had a lot to learn about how stubborn Billy could be.

His daughter, Breeze Fielding, Billy’s new thirteen-year-old stepsister, knew differently. She had seen Billy’s stubborn streak in action when, at their parents’ wedding, he refused to wear the shiny shoes that came with the rented tuxedo and insisted on wearing his baseball cleats instead. He said it was a garden wedding anyway, and the cleats gave him better traction as he came down the aisle carrying the rings. That was okay with Breeze, though, because at the wedding, she wore motorcycle boots on her feet, blue streaks in her hair, and a lot of thrift store velvet in between.

“Come on, folks. Let’s go inside,” Breeze said. “It’s not like he’s going to stay in there forever. As soon as he has to pee, he’ll come flying in the front door doing the I-gotta-go dance.”

“Point well taken, Breeze,” her father answered. “Your thought process is as clean as a well-flossed tooth.” Dr. Fielding was a dentist, and nothing made him happier than the subject of healthy teeth.

Billy looked out the window of the car and studied his new house. It gave him the creeps. Every other house on the block was normal: beige stucco with a lawn in front, a basketball hoop in the driveway, and a brick path leading up to a painted front door. Not this house, though. No, this house had a mini orange grove where the front lawn should be, with actual dead oranges rotting on the ground. Not only did it not have a basketball hoop in the driveway, it didn’t even have a driveway. Why should it? It was built before cars were invented, when Los Angeles was just a small town by a river. And it looked it, too, with its peeling paint and rusty iron door knocker shaped like the head of a horse. His mother and stepfather said it was an architectural treasure. Billy thought it should be put back in the treasure chest and dropped to the bottom of the river.

It was too late for that, though. The moving truck had already arrived, and several burly men were starting to unload the hundreds of boxes that contained the family’s entire life. Billy pulled down the armrest and leaned back, watching the neatly labeled parade of cardboard boxes go by. Pots and Pans, Billy’s Baseball Cards, Clean Towels, Towels to Be Washed, Parrot Cage Without Bird, Assorted Hair Products. Billy knew that box smelled like coconut mango honey, his mom’s favorite shampoo scent. He always knew whenever she had just washed her hair, because every bee in the neighborhood wanted to land on her head.

“Hey, weirdo!”

Billy heard a muffled voice followed by a sharp rat-a-tat-tat on the window. He whipped around and saw a face pressed up against the glass like a suction cup. It was a big, doughy face that spread itself all over the window.

“Your car’s back wheel is on our property by a tenth of an inch,” the face said. “I just measured it. I’m going to have to report this to the police.”

“Pardon me,” Billy said. “It’s hard to hear what you’re saying.”

“I said move it or I’m reporting you for trespassing,” the face shouted.

Billy rolled down the window just a crack, enough to let sound in. He peered out and saw that the face belonged to a boy about his age, tall and bulky with binoculars around his neck and a retractable tape measure in his hand.

“I will move it,” Billy said, “in five years, when I get my license.”

“Oh,” the big kid said. “So you’re one of those. New, and a wise guy. I’d ask your name, but it’s a waste of my time, because you’re not going to be in that house long anyway.”

“What are you talking about? My parents just bought it.”

“The last family stayed a year. The one before that, six months, tops.”

“Why? Because they all met you?”

The kid let out a laugh that was something between a snort and a grunt, and sprayed a little snot on the window.

“That was funny, toad face.”

“My name’s Billy. Billy Broccoli to be exact. I know you’re probably going to laugh at that — everybody does — but we just had the car washed, so try to keep yourself from snorting.”

“Funny again. That’s two for you. I’m Rod Brownstone. And I know everything about this neighborhood. You don’t want to mess with me.”

Billy got out of the car, and as he did, he realized that Rod Brownstone was almost twice his size, not only in mouth but in body. Rod’s head, which sported a thick cluster of black, lumpy hair, was as big as a small boulder and his body seemed rock hard, too. Billy felt smaller than usual, which wasn’t easy because he was short to begin with. Even if his name didn’t start with a B, he would still have been at the front of the line in school, because he was the shortest boy in class. His mom reassured him that a growth spurt was in his future, but he was starting to seriously doubt that.

Rod picked up his binoculars and focused them directly on Billy.

“What are you looking at?” Billy asked him.

“Just standard police practice when gathering intel to keep the neighborhood safe.”

“I’m not exactly a threat, Brownstone.”

“I’ll be the judge of that,” Rod snorted. “Just remember, Broccoli. I’ve got you in my sights.”

Billy backed away from Rod, feeling both intimidated and weirded out. This guy wasn’t what you’d call a welcome wagon. In fact, he made Billy even more nervous about his new house than he already was. As he backed up, he bumped into one of the movers carrying a box labeled Billy’s Baseball Gear. It was upside down and the tape holding the lid closed bulged, as if the contents might fall out any second.

Billy wasn’t very good at baseball, b

ut he loved it and always took care of his equipment, in case one day his skills suddenly grew to match his love of the game.

“Excuse me, sir,” Billy said. “I’ll take that. I don’t want my gear to fall.”

It was a perfect excuse to get away from Rod Brownstone. The mover shrugged and handed the box to Billy, who took it and hurried up to the front door.

“Well, look who’s decided to show up.” Breeze stood in the entryway, holding her cell phone between her ear and her shoulder while spiking her hair in the reflection from the latched glass peephole in the front door.

“I wouldn’t be here, except our next-door neighbor was just about to put me under house arrest,” Billy said to her.

“I know that kid Rod,” Breeze answered. “He’s on the football team at school. If I were you, I’d hang out with him and find out what his secret is. Maybe he can un-scrawny-ize you.”

“Thanks for the vote of confidence, Breeze. Can you just tell me where my room is?”

“Last one at the end of the hall. We flipped a coin, but a certain somebody was sitting in the car, so you got what you got. Don’t worry, it’ll grow on you. Or not.”

Billy made his way down to the end of the hall. His mother and stepfather were in their room, trying to find enough space in the closet for all their clothes. Like most dentists, Dr. Fielding had mostly white short-sleeved shirts, but unlike other dentists, he had an extensive collection of colored ties, each one featuring a big smiling tooth in the middle. Some even had captions with the tooth saying things like “You drill me!” or “You’re so filling” or “Decay Stinks.” Dr. Fielding thought they were hilarious.

Billy passed by Breeze’s room, a large airy space that had its own little patio. When he got to his door, he adjusted his grip on the box, pushed the door open with his rear end, and backed into the room. It was a good thing, too, because had he walked in frontways, he would have taken one look around and passed out right then and there.

The room was lavender and pink. And to make matters worse, there were ponies chasing rainbows on the wallpaper. For furniture, there was a lavender dresser, a pink wicker desk, and a bed with a lavender headboard that had the words Sleep Tight, Sweetie Pie chiseled into it.

Billy dropped the box, dropped his jaw, and screamed. “It’s a nightmare in the middle of the morning!”

“What’s the matter, honey?” his mom called as she came running down the hall.

“Mom, this room is having a pink attack.”

“I know it’s not exactly your color scheme, sweetie. But don’t worry, we have plans.”

“Really? To seal it up with brick? Because I’m all in favor of that.”

By that time, Dr. Fielding had arrived on the scene.

“Bill,” he said. “I imagined that you and I would take this on as a do-it-yourself project. You pick the color, we’ll paint it together.”

“Can we start, like, now, Bennett, because I can’t go in there ever again.”

Breeze, hearing the commotion, came down to enjoy the fireworks.

“Hey, you could sleep in the car,” she suggested to Billy. “You seem to like it in there. A blow-up mattress, some potato chips, and a mini TV? A guy could get used to that.”

“This isn’t funny, Breeze. I couldn’t possibly invite a new friend over to this room.”

“And how many new friends do you have exactly? Correct me if I’m wrong, but I thought it was none.”

“I have plans to build an army of friends,” Billy said.

“I guess that doesn’t include your pal next door. You two didn’t seem to hit it off.”

Breeze’s phone rang again and she headed back to her room, laughing and talking with one of her hundreds of friends. Billy envied her. Their new house was in the district she and Bennett had been living in before the wedding, so she didn’t have to change schools. She could just continue at Moorepark Middle School with nothing more than a change-of-address form. But for Billy, the move to this house meant everything would be different. He had to leave his old neighborhood and his old friends and his old school and start all over again — and at Moorepark, where his mother was principal. Just the thought of that made his head spin.

Billy decided that some food in his belly might settle him down, so he walked down the hall and headed for the kitchen, hoping his mother had stocked the refrigerator with string cheese and apple juice, his favorite snacks. She had.

The snack made him feel much better and he returned to his room, determined to make himself adjust to the purple mist around him. But his good mood disappeared when he entered his room. His baseball stuff, including his glove, two aluminum bats, his cleats, his sliding shorts, and his three signed game balls, had somehow found their way out of the box and were sitting in a perfectly formed circle on the carpet. This was unacceptable. He tore down the hall, shouting Breeze’s name.

“Stop yelling,” she said, poking her head out of her room. “What’s your problem?”

“Let’s get this straight, Breeze. I’ve only asked you two things since I’ve known you. One, don’t touch my baseball stuff. And two, don’t touch my baseball stuff.”

“Why would I even want to touch your infested baseball gear? It reeks.”

“Don’t tell me it wasn’t you.”

“Billy, I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Follow me and I’ll show you.”

Billy marched Breeze down to his room and pointed to the center of his carpet.

“There,” he said. “I never gave you permission to take my stuff out of the box.”

“It’s not out of the box, genius.”

Billy whipped around and to his utter amazement, all his baseball gear was neatly packed in the cardboard box, and the lid was taped shut.

“Don’t bother me again with your stupid jokes,” Breeze said. “You’re not funny.”

Billy didn’t answer. He couldn’t. All he could do was stare silently at that box. Was he going nuts? He could have sworn that his baseball gear had gotten out of that box and then put itself back.

But how?

CHAPTER 2

After Breeze left, Billy stood there staring at the box. He was a logical person and he knew that baseball equipment didn’t just unpack and repack itself. As he tried to come up with a rational explanation for this mystery, his mother came into his room, carrying an armload of clothes on hangers.

“Honey, these things need to be hung up in your closet nicely,” she said. The stack of clothes was so big that all Billy could make out was the top of her brownish curly hair and the toes of her red cowboy boots. “You start a new school on Monday and you don’t want to show up on the first day with wrinkly clothes.”

“Just drop them on the rug, Mom. I’ll get to it later.”

“I want you to start on it right away. Here, I’ll show you how.”

She flopped the stack of clothes on the pink desk, picked up three or four hangers, and started for the closet.

“Mom, this is totally unnecessary. I’m one of the great hanger-uppers.”

“Really? What about that pile of clothes in your old room that you referred to as Smelly Mountain? I didn’t see much in the way of hanging up going on there.”

Mrs. Broccoli-Fielding pulled the closet door open and stepped inside. Her nose twitched.

“Billy, you know the rules. You’re not supposed to have food in your room.”

“Mom, I haven’t eaten anywhere but in the kitchen. Honest.”

“Then why does your entire closet smell of orange juice?”

Billy walked to the closet and took a whiff. She was right. It smelled like one of those trees in the front yard.

“I guess the girl who had this room before me must have liked to drink orange juice in the closet.” He shrugged. “She probably did it to get away from all the purple and pink.”

“Okay, young man, start hanging,” Billy’s mom said. “And just to show you that moving day can be fun, we’ve ordered p

izzas for dinner, including your favorite, pineapple bacon.”

“Breeze better not touch that,” Billy said, his mouth starting to water.

“Honey, Breeze is vegetarian.”

“Since when?”

“Since this morning at ten. She says she feels better already.”

Billy’s mother left, and with a deep sigh, he started to put his clothes away. The first hanger he grabbed held his baseball jersey from last season. It looked almost new, since mostly he sat on the bench and didn’t get to play much. Billy hooked the hanger on the wooden bar in the closet — but when he turned to get another piece of clothing, he heard a noise that sounded like the hanger scuffling along the bar on its own. Billy glanced into the closet and it seemed to him that his baseball jersey had moved.

No, that couldn’t be.

Just to make sure, he turned his back to the closet, then spun around with lightning speed, half expecting to catch his jersey moving by itself. But it just hung there, smelling like orange juice, presenting no danger to anyone.

Billy was relieved, because he was not a guy who loved danger. At the top of his list of least favorite things were scary movies, bumpy airplane rides, bungee jumping, roller coasters, creepy or sad clowns, and anything that popped up at him. As a matter of fact, when he was five and a half, he’d smashed his jack-in-the-box to bits with his slipper.

He spent the rest of the afternoon putting his clothes away and organizing his room. By the time he finished, ate some pizza, and crawled into bed that night, he was exhausted. But even though he was bone tired, he just couldn’t drift off. He missed his old room in his old house. And he worried about starting a new school on Monday and having to make all new friends.

Billy rolled to his side and stared at the closet door, focusing on the brass doorknob. He had read once that if you stared at something for a really long time and didn’t even let yourself blink, it calmed you down enough so that you eventually fell asleep without knowing it. He must have stared at that doorknob for seven minutes, but nothing happened. It just hung there on the edge of the door, being all knobby. He was about to give up when suddenly he saw something that made his stomach flip and his blood run cold.

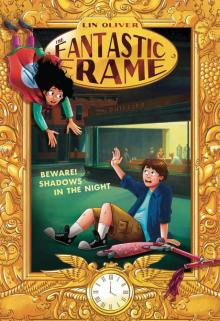

Beware! Shadows in the Night

Beware! Shadows in the Night Almost Identical #1

Almost Identical #1 Two-Faced #2

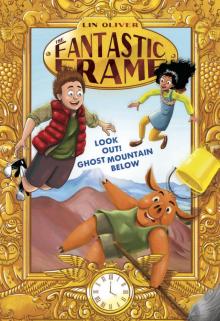

Two-Faced #2 Look Out! Ghost Mountain Below

Look Out! Ghost Mountain Below Zero to Hero

Zero to Hero Always Dance with a Hairy Buffalo

Always Dance with a Hairy Buffalo Danger! Tiger Crossing

Danger! Tiger Crossing Twice As Nice

Twice As Nice Double-Crossed

Double-Crossed Splat! Another Messy Sunday

Splat! Another Messy Sunday The Shadow Mask

The Shadow Mask